TL;DR: In some circumstances, you may find usable Kerberos TGTs on a system you compromised - these allow you to impersonate a user that already changed its password (e.g. because the user got suspicious or a PAM solution is in place).

Intro

On a recent project, I was tasked with the usual goal: Start from the ground and find a way to take over the company - in the end, if possible, somehow become Domain Admin. Getting started was tough, but after some time I got my hands on a few admin accounts and had a way to take control of the Domain Admins - but the way involved resetting the password of a service account. Unless I do not have a very good reason to perform the password change or the explicit “Do it!” from the customer, I prefer finding another way. Lurking for a few days on the machines I gained access so far, I discovered two accounts that logged on recently. They both provided a simpler way to become Domain Admin because they were allowed to write the Domain Admin group directly - Jackpot!

So, I dumped the credentials, opened a local mmc using one of the accounts and was about calling it a day, when suddenly Windows refused the credentials of the account because they were wrong.

I double checked my data and also tried the other account, but unfortunately without success.

Using the Sysinternals AD Explorer I checked the pwdLastSet attribute of both accounts.

The passwords of both accounts had been changed a few moments after dumping them, and because I had some operational struggles on the server I was not fast enough to use the credentials when they were still valid.

At that point, I remembered that the customer started a CyberArk roll out recently and according to their Active Directory OU, these accounts seemed to be managed by CyberArk already. Now, I was quite resigned - I managed to dump highly privileged accounts but the credentials changed faster than I could abuse them.

Digging deeper

CyberArk is a so called privileged access management (PAM) solution and one of its central ideas is to have the credentials managed by the appliance. In the best case, administrators will never see any passwords again, instead CyberArk takes care about login, logout and password rotation using one of the accounts in the account pool managed by the appliance. For the accounts I dumped, this means that someone was working on the server via CyberArk and after logging out, CyberArk automatically changed the password of the accounts to a new random value.

After silently giving them props for having their accounts protected by such a solution, I went on with the test and focused on other topics, but something in the back of my head kept working on it. I spent a lot of time with Kerberos in the last few months, and one idea that came up was the following: Why can’t I just use the obtained NTLM hashes to perform a overpass-the-hash (See @gentilkiwi’s BlackHat 2014 Paper)?

Wrong direction…

As I’m in possession of the NTLM hash, I should be actually able to forge an arbitrary Kerberos ticket offline, but neither Mimikatz nor Rubeus contained the capabilities to do so.

The closest was Mimikatz’s kerberos::golden or Rubeus’ asktgt, but the first one works only if the accounts are service accounts and the second one will communicate with a domain controller in order to retrieve the ticket - but this will not work, since the credentials have already changed.

I thought a bit longer about the idea and realized it is total nonsense.

The user’s Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT), which is used to request other Kerberos tickets, is encrypted using the krbtgt key, therefore there is no way to fake the ticket without the krbtgt hash.

If you obtain the krbtgt credentials, you don’t have to become Domain Admins anymore because you can already impersonate any user via kerberos::golden.

Right direction!

Nevertheless, I realized that there is a good chance that a valid TGT for each of the accounts is still in memory. I dumped the credentials two hours ago and the regular life time of a TGT is ten hours, therefore I jumped again on the server and used Rubeus to extract all Kerberos tickets.

There it was: The TGT of the account I needed to become Domain Admin!

After some fiddling with text editors, max line length in Powershell and base64 (why doesn’t Rubeus just extract the Kirbi files but line wrapped Base64?!), I was able to inject the TGT into the memory of my virtual machine.

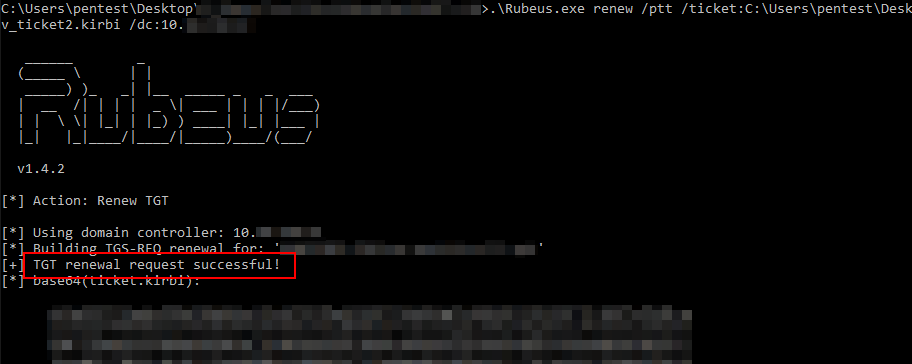

I tried to renew the ticket with Rubeus, this worked fine and I was confident to go.

Unfortunately, using mmc didn’t work, but net use a: \\randomserver_i_shouldnt_have_access_to\c$ mounted me a C$ share on a:, so the issue is probably mmc not solely using Kerberos.

Fortunately, PowerSploit has a function called Add-DomainGroupMember.

This worked, I was able to add one of my test accounts to Domain Admins without further obstacles!

Conclusion

Apart from reaching my goal, I bypassed one of CyberArk’s marketing promises. The fact that passwords change after every use gives operators and security people a good feeling regarding security of the accounts. Their sales pitches probably do not include hints that their password rotation may be undermined by the way Kerberos works.

This was also the first time I realized, that password changes are not a measure that is effective immediately. Probably every penetration tester knows the situation where a target changed a password the day after it was dumped (because the victim got suspicious, had to change passwords, …). There is a high chance these credentials can still be used, at least for up to a week! Just make sure that you also extract the Kerberos TGTs present on the system. I think this is something many penetration testers are not aware of, albeit this is just how Kerberos works.

Fixing the issue

To be honest, I have no clue how to fix this. There is no vulnerability involved, the “attack” just abuses how Kerberos works. Maybe immediate rotation is not the (sole) solution to the credential theft issue, instead additional measures like locking the account if it is not used may help to mitigate this problem. I don’t know if Windows writes log events that indicate tickets with expired credentials or similar, but maybe it is possible to detect this anomaly via log analysis, too.

Kudos

This attack (or at least me performing it) would not have been possible without the great work of Benjamin Delpy (@gentilkiwi) and Will Schroeder (@harmj0y) as well as numerous other security researchers and contributors to the Rubeus, Mimikatz and Powersploit projects. They do not only openly share their tools, but also the knowledge behind. Thank you!